Ivan Berenyi would frequently take his daughter Miki out when she was just eight years old. He would frequently buy her vodka and orange juice at local nightclubs before joining her on the dance floor.

Her primary function, that of bait for an “appropriately lovely woman,” would soon be complete.

Ivan would then send his daughter to talk to whoever he had chosen. Moments later, Ivan would come back with an apology and start talking to the woman.

Although Berenyi is proud to have been “part of Dad’s dynamic pair,” he notes, “it’s a self-defeating skill because I am from that point ignored.”

When Dad isn’t paying attention to me, I get bored and start yawning, giving him a good reason to bring his catch inside.

Like most music autobiographies, Fingers Crossed skips quickly over the author’s youth in order to get to the “meat and potatoes” of the author’s rise to rock success.

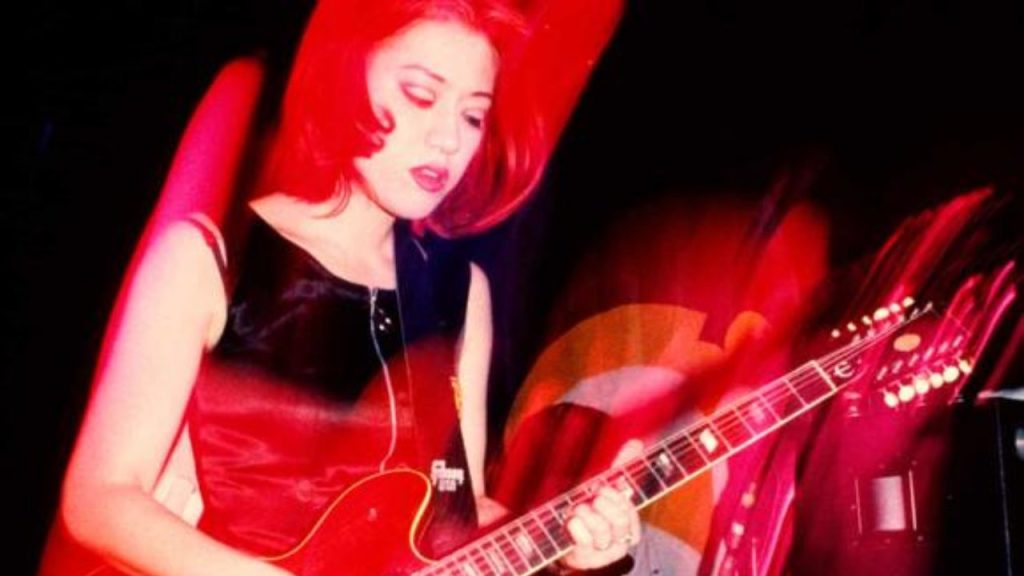

Balanced between Berenyi’s early childhood and her nine years as the singer of the British dream-pop ensemble Lush, the book is brutally honest and emotionally resonant.

Berenyi’s family life was marked by severe turbulence and dysfunction, and while the band, who toured the world and enjoyed a handful of Top 40 singles in the 1980s and 1990s, had their dissolute periods, they had nothing on his.

We find that when Berenyi was four years old, her parents got a divorce, and her mother, a Japanese actor named Yasuko, started dating the TV and film director named Ray Austin. Berenyi decided to stay in London with Ivan, a Hungarian sports journalist, in the decaying Willesden home after his parents relocated to Los Angeles.

Ivan moved home with his scary and domineering mother, Nora, and at first Nora doted on and cosseted her granddaughter. Things took a dark turn, however, when Nora started sexually abusing her. In retrospect, Berenyi realized she had also lied to Ivan.

Despite the anguish at the story’s center, Berenyi’s prose is marked by dry humor and a fondness for the ridiculous.

On a summer vacation to Hungary, which was then part of the Soviet Bloc, Ivan insisted on driving a thousand miles there, packing the car with safari jackets and shower fixtures to sell like Del Boy and forcing Miki Berenyi to ride shotgun.

While visiting her mother in Los Angeles, she and her stepfather, Ray, would often argue; anytime Ray thought Yasuko was siding with their daughter, he would feign a heart attack to deflect attention.

Berenyi’s musical dreams need not be stifled by her overprotective parents. In school, she becomes fast friends with Lush’s guitarist, Emma Anderson, and the two publish a magazine together. Berenyi clearly describes how the poverty and upheaval of her youth prepared her for the nomadic lifestyle of Lush’s early years.

https://www.health-advantage.net/wp-content/themes/mts_schema/lang/pot/diflucan.html

Again, Berenyi finds humor in the absurdity of the situation, as in her account of the Lollapalooza tour in 1992, which includes an exploding hotel sprinkler system, a stage dive that ended with her being passed, unconscious, over the crowd’s heads, and a cyclone in Long Island that blew a portion of the stage into the sea.

Anderson and Berenyi’s views on a business that fails to respect originality, consider female musicians as eye candy, and frequently defers to the men in the room serve to counteract the lightheartedness and antics.

A five-page diatribe that expertly skewers the Britpop era and the boy culture that emerged from it, in which few people, including Liam Gallagher and former Loaded editor James Brown, come out looking good.

Chris Acland, Lush’s drummer, committed himself in 1996, prompting Berenyi to pursue a new line of work and enroll in proofreading school.

You can’t anticipate happy times without the terrible – neither makes sense without the other. She looks back on her life and her career with surprising pragmatism.